The Story of a Unit in Unit Tests

In the previous part of this article, you could see some bad, though popular, test samples. But I’m not a professional critic (also known as a troll, or a hater), to grumble about without having anything constructive to say. Years of TDD have taught me more than just how bad the things can go. There are many simple but effective tricks, that can make you test-life much easier.

Imagine this: you have a booking system for a small conference room in a small company. By some strange reason, it has to deal with off-line booking. People post their booking requests to some frontend, and once a week you get a text file with working hours of the company, and all the bookings (for what day, for how long, by whom, submitted at what point it time) in random order. Your system should produce a calendar for the room, according to some business rules (first come, first served, only in office business hours, that sort of things).

As part of the analysis, we have a clearly defined input data, and expected outcomes, with examples. Beautiful case for TDD, really. Something that sadly never happens in the real life.

Our sample test data looks like this:

class TestData {

static final String INPUT_FIRST_LINE = "0900 1730\n";

static final String FIRST_BOOKING = "2011-03-17 10:17:06 EMP001\n" +

"2011-03-21 09:00 2\n";

static final String SECOND_BOOKING = "2011-03-16 12:34:56 EMP002\n" +

"2011-03-21 09:00 2\n";

static final String THIRD_BOOKING = "2011-03-16 09:28:23 EMP003\n" +

"2011-03-22 14:00 2\n";

static final String FOURTH_BOOKING = "2011-03-17 10:17:06 EMP004\n" +

"2011-03-22 16:00 1\n";

static final String FIFTH_BOOKING = "2011-03-15 17:29:12 EMP005\n" +

"2011-03-21 16:00 3";

static final String INPUT_BOOKING_LINES =

FIRST_BOOKING +

SECOND_BOOKING +

THIRD_BOOKING +

FOURTH_BOOKING +

FIFTH_BOOKING;

static final String CORRECT_INPUT = INPUT_FIRST_LINE + INPUT_BOOKING_LINES;

static final String CORRECT_OUTPUT = "2011-03-21\n" +

"09:00 11:00 EMP002\n" +

"2011-03-22\n" +

"14:00 16:00 EMP003\n" +

"16:00 17:00 EMP004\n" +

"";

}

So now we start with a positive test:

BookingCalendarGenerator bookingCalendarGenerator = new BookingCalendarGenerator();

@Test

public void shouldPrepareBookingCalendar() {

//when

String calendar = bookingCalendarGenerator.generate(TestData.CORRECT_INPUT);

//then

assertEquals(TestData.CORRECT_OUTPUT, calendar);

}

It looks like we have designed a BookingCalendarGenerator with a “generate” method. Fair enough. Lets add some more tests. Tests for the business rules. We get something like this:

@Test

public void noPartOfMeetingMayFallOutsideOfficeHours() {

//given

String tooEarlyBooking = "2011-03-16 12:34:56 EMP002\n" +

"2011-03-21 06:00 2\n";

String tooLateBooking = "2011-03-16 12:34:56 EMP002\n" +

"2011-03-21 20:00 2\n";

//when

String calendar = bookingCalendarGenerator.generate(TestData.INPUT_FIRST_LINE + tooEarlyBooking + tooLateBooking);

//then

assertTrue(calendar.isEmpty());

}

@Test

public void meetingsMayNotOverlap() {

//given

String firstMeeting = "2011-03-10 12:34:56 EMP002\n" +

"2011-03-21 16:00 1\n";

String secondMeeting = "2011-03-16 12:34:56 EMP002\n" +

"2011-03-21 15:00 2\n";

//when

String calendar = bookingCalendarGenerator.generate(TestData.INPUT_FIRST_LINE + firstMeeting + secondMeeting);

//then

assertEquals("2011-03-21\n" +

"16:00 17:00 EMP002\n", calendar);

}

@Test

public void bookingsMustBeProcessedInSubmitOrder() {

//given

String firstMeeting = "2011-03-17 12:34:56 EMP002\n" +

"2011-03-21 16:00 1\n";

String secondMeeting = "2011-03-16 12:34:56 EMP002\n" +

"2011-03-21 15:00 2\n";

//when

String calendar = bookingCalendarGenerator.generate(TestData.INPUT_FIRST_LINE + firstMeeting + secondMeeting);

//then

assertEquals("2011-03-21\n15:00 17:00 EMP002\n", calendar);

}

@Test

public void orderingOfBookingSubmissionShouldNotAffectOutcome() {

//given

List shuffledBookings = newArrayList(TestData.FIRST_BOOKING, TestData.SECOND_BOOKING,

TestData.THIRD_BOOKING, TestData.FOURTH_BOOKING, TestData.FIFTH_BOOKING);

shuffle(shuffledBookings);

String inputBookingLines = Joiner.on("\n").join(shuffledBookings);

//when

String calendar = bookingCalendarGenerator.generate(TestData.INPUT_FIRST_LINE + inputBookingLines);

//then

assertEquals(TestData.CORRECT_OUTPUT, calendar);

}

That’s pretty much all. But what if we get some rubbish as the input. Or if we get an empty string? Let’s design for that:

@Test(expected = IllegalArgumentException.class)

public void rubbishInputDataShouldEndWithException() {

//when

String calendar = bookingCalendarGenerator.generate("rubbish");

//then exception is thrown

}

@Test(expected = IllegalArgumentException.class)

public void emptyInputDataShouldEndWithException() {

//when

String calendar = bookingCalendarGenerator.generate("");

//then exception is thrown

}

IllegalArgumentException is fair enough. We don’t need to handle it in any more fancy way. We are done for now. Let’s finally write the class under the test: BookingCalendarGenerator.

And so we do. And it comes out, that the whole thing is a little big for a single method. So we use the power of Extract Method pattern. We group code fragments into different methods. We group methods and data those operate on, into classes. We use the power of Object Oriented programming, we use Single Responsibility Principle, we use composition (or decomposition, to be precise) and we end up with a package like this:

We have one public class, and several package-scope classes. Those package scope classes clearly belong to the public one. Here’s a class diagram for clarity:

Those aren’t stupid data-objects. Those are full fledged classes. With behavior, responsibility, encapsulation. And here’s a thing that may come to our Test Driven minds: we have no tests for those classes. We have only for the public class. That’s bad, right? Having no tests must be bad. Very bad. Right?

Wrong.

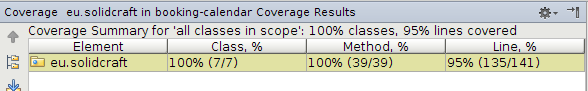

We do have tests. We fire up our code coverage tool and we see: 100% methods and classes. 95% lines. Not bad (I’ll get to that 5% of uncertainty in the next post).

But we have only a single unit test class. Is that good?

Well, let me put some emphasis, to point the answer out:

It’s a UNIT test. It’s called a UNIT test for a reason!

The unit does not have to be a single class. The unit does not have to be a single package. The unit is up to you to decide. It’s a general name, because your sanity, your common sense, should tell you where to stop.

So we have six classes as a unit, what’s the big deal? How about if somebody wants to use one of those classes, apart from the rest. He would have no tests for it, right?

Wrong. Those classes are package-scope, apart from the one that’s actually called in the test. This package-scope thing tells you: “Back off. Don’t touch me, I belong to this package. Don’t try to use me separately, I was design to be here!”.

So yeah, if a programmer takes one of those out, or makes it public, he would probably know, that all the guarantees are voided. Write your own tests, man.

How about if somebody wants to add some behavior to one of those classes, I’ve been asked. How would he know he’s not breaking something?

Well, he would start with a test, right? It’s TDD, right? If you have a change of requirements, you code this change as a test, and then, and only then, you start messing with the code. So you are safe and secure.

I see people writing test-per-class blindly, without giving any thought to it, and it makes me cry. I do a lot of pair-programming lately, and you know what I’ve found? Java programmers in general do not use package-scope. Java programmers in general do not know, that protected means: for me, all my descendants, and EVERYONE in the same package. That’s right, protected is more than package-scope, not less a single bit. So if Java programmers do not know what a package-scope really is, and that’s, contrary to Groovy, is the default, how could they understand what a Unit is?

How high can I get?

Now here’s an interesting thought: if we can have a single test for a package, we could have a single test for a package tree. You know, something like this:

We all know that packages in Java are not really tree-like, that the only thing those have with the directory structure is by a very old convention, and we know that the directory structure is there only to solve the collision-of-names problem, but nevertheless, we tend to use packages, like if the name.after.the.dot had some meaning. Like if we could hide one package inside another. Or build layers of lasagne with them.

So is it O.K. to have a single test class for a tree of packages?

Yes it is.

But if so, where is the end to that? Can we go all the way up in the package tree, to the entry point of our application? Those… those would be integration tests, or functional tests, perhaps. Could we do that? Would that be good?

The answer is: it would. In a perfect world, it would be just fine. In our shitty, hanging-on-the-edge-of-a-knife, world, it would be insane. Why? Because functional, end-to-end test are slow. So slow. So horribly slow, that it makes you wanna throw them away and go some place where you would not have to be always waiting for something. A place of total creativity, constant feedback, and lightning fast safety.

And you’re back to unit testing.

There are even some more reasons. One being, that it’s hard to test all flows of the application, testing it end-to-end. You should probably do that for all the major flows, but what about errors, bad connections, all those tricky logic parts that may throw up at one point or another. No, sometimes it would be just too hard, to set up the environment for integration test like that, so you end up testing it with unit tests anyway.

The second reason is, that though functional tests do not pour concrete over your code, do not inhibit your creativity by repeating you algorithm in the test case, they also give no safety for refactoring. When you had a package with a single public class, it was quite obvious what someone can safely do, and what he cannot. When you have something enclosed in a library, or a plugin, it’s still obvious. But if you have thousands of public classes, and you are implementing a new feature, you are probably going to use some of them, and you would like to know that they are fine.

So, no, in our world, it doesn’t make sense to go with functional tests only. Sorry. But it also doesn’t make sense to create a test per class. It’s called the UNIT test, for a reason. Use that.