In this short article, we will have a look at how we can bypass Kotlin’s native null-safety with sun.misc.Unsafe, and see why it can be dangerous even if we are not messing up with it directly.

Mythical sun.misc.Unsafe

The sun.misc.Unsafe class is an internal JVM tool for executing low-level operations like off-heap memory allocation, thread parking, CAS, and much more.

This class is like one of those scary computer game creatures that are there only to intimidate us, in theory, we can’t get close because they are part of the environment, but it’s often possible by exploiting glitches or holes.

If we try to access the Unsafe instance, we encounter a private constructor and a static getUnsafe() method that raises a SecurityException practically every time we call it:

public final class Unsafe {

private static final Unsafe theUnsafe;

// ...

private Unsafe() {}

@CallerSensitive

public static Unsafe getUnsafe() {

Class var0 = Reflection.getCallerClass();

if (!VM.isSystemDomainLoader(var0.getClassLoader())) {

throw new SecurityException("Unsafe");

} else {

return theUnsafe;

}

}

}

So, in theory, it’s guarded by a strong encapsulation, and an exception being thrown on every getUnsafe() call… but we do have the Reflection mechanism, and we can easily bypass those:

private fun getUnsafe(): Unsafe {

return Unsafe::class.java.getDeclaredField("theUnsafe")

.apply { isAccessible = true }

.let { it.get(null) as Unsafe }

}

Mighty Unsafe.allocateInstance()

This method allocates an empty instance of a given class directly on the heap ignoring field initialization and constructors.

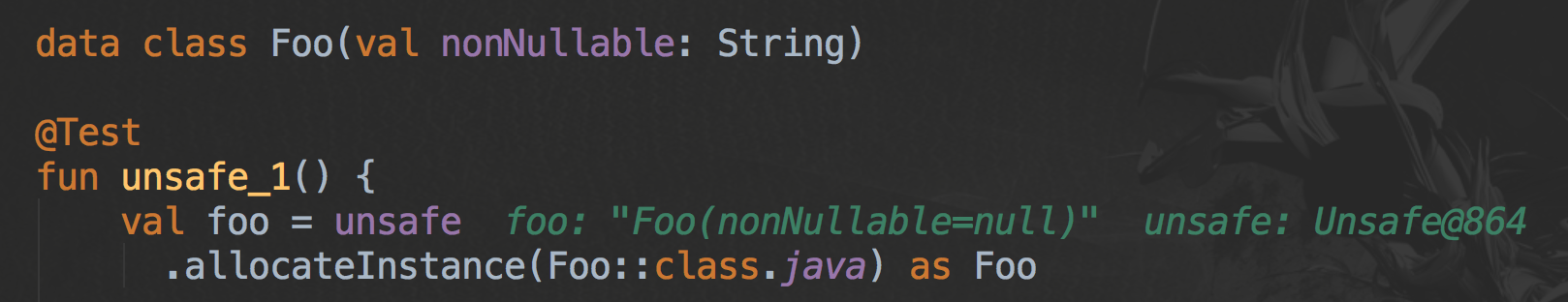

And this allows us, indeed, to effectively bypass Kotlin’s safety checks:

A cool thing to do on Friday’s evening, but what about just not using Unsafe and staying (null)safe?

Problem: Unsafe in External Libraries

The problem is that most Java libraries were written with Java in mind, where using Unsafe for certain scenarios is slightly less unsafe than it is e.g., for Kotlin.

This is especially the case with serialization/deserialization libraries – one of such is Google’s Gson which internally uses Unsafe for instantiating objects in certain situations – which is totally acceptable for Java.

If we start using it in Kotlin, we indeed might end up with an undesired behaviour observed above:

@Test

fun unsafe_2() {

val foo = Gson().fromJson("{}", Foo::class.java)

assertThat(foo.nonNullable).isNull()

}

In this case, we simply need to perform checks manually after instantiation, which is not super problematic – what’s problematic is the lack of consciousness that this happens, which can cost much.

Are you sure the library you are using is not doing that internally?

Code snippets can be found on GitHub.

Key Takeaways

- Kotlin’s null-safety does not go beyond objects’ initialization phase and is bypassable

- External libraries that use Unsafe internally can do that too – it’s important to be aware of this